THE DETAILS

Video testimony from Thursday included

QUINCY — “Her severe head injuries were due to abusive head trauma and led to her death.”

That was the opinion of Dr. Channing Petrak, a child abuse pediatrician from Peoria, as to how 2-month-old Airyana Hoffman died on Jan. 22, 2018, after being found unresponsive in her mother’s apartment two days earlier.

“Airyana had natural disease process that included an infection. Her body overreacted to that infection in a process known as sepsis, and as part of that process, she developed blood clots that traveled to her brain and caused her to have a stroke.”

That was the opinion of Dr. Jane Turner, a forensic pathologist from St. Louis, as to how Airyana died.

Both opinions were given to the nine-woman, three-man Adams County jury on Thursday in Adams County Circuit Court. The jury will be tasked with determining which theory they deem most believable when they are given the Travis Wiley first-degree murder case for deliberation as expected around mid-day Friday.

Wiley, 35, is accused of shaking Airyana on Jan. 20, 2018, and she died two days later at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital in St. Louis. Wiley was arrested June 20, 2018, and remains in the Adams County Jail on a $5 million bond. If he’s found guilty, a minimum sentence for first-degree murder would be 20 years in the Illinois Department of Corrections, with a maximum sentence of 60 years.

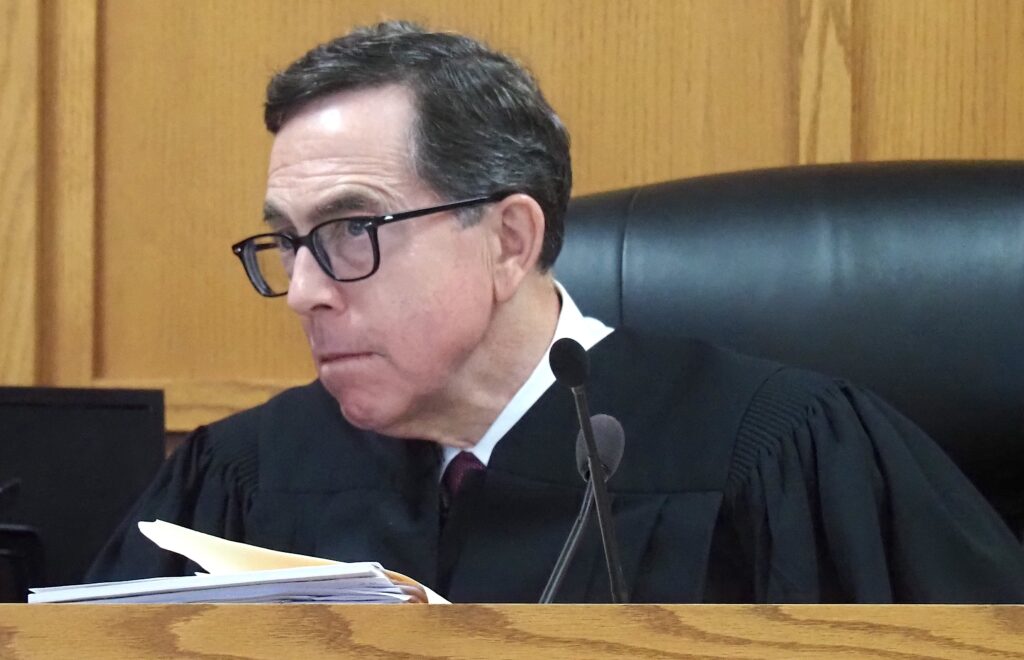

Both the prosecution and the defense rested on Thursday. Wiley told Judge Michael Atterberry he was giving up his right to testify. Closing arguments are expected to begin at 9 a.m. Friday.

Turner says process of Airyana’s death started before Jan. 20

The testimony of each woman was detailed. Petrak spent about two hours on the stand in the morning, and Turner was questioned for more than 3½ hours. However, the give-and-take between Turner and Special Prosecutor Jon Barnard was unquestionably the most spirited.

However, Chief Public Defender Todd Nelson first asked questions of Turner for about 75 minutes. Turner worked for 18 years in the St. Louis Medical Examiner’s Office. Along with her role as a forensic pathologist, she also has her own consulting business on the side.

Turner said she reviewed medical records from Blessing Hospital in Quincy and Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital in St. Louis, as well as police investigative reports, a grand Jury transcript, records from St. Louis Medical Examiner’s Office and autopsy photographs and autopsy slides.

Turner said the slides showed blood clots pre-existed in Airyana before she was admitted to Blessing on Jan. 20.

“This was a process that started before Jan. 20 but became critical on Jan. 20,” she said.

Turner said the first chest X-ray of Airyana at Blessing less than an hour before she was admitted there showed she had abnormalities of her lungs consistent with pneumonia. A lab study showed she had a “markedly elevated” white blood cell count, and she also had a low body temperature, a possible indicator of infection. A urinalysis showed Airyana had ketones, which develop when a person has diabetic ketoacidosis, and glucose in her urine.

Turner called testing done at Cardinal Glennon “limited,” explaining no testing was done for viruses or bacteria — which would have told her what organisms could have been involved in a sepsis reaction. She said blood and cerebral spinal fluid should have been collected. A lung biopsy should have been performed.

Turner reviews slides showing evidence of pneumonia, clots

Turner said clotting was found in the skull cavity, and it had been going on “many days” before Jan. 20, 2018. She said small blood clots were found in blood vessels in different organs — the lung, the kidney, the eyes and the brain.

Nelson asked about a D-Dimer test, which Turner explained shows evidence of blood clotting in the body. She said a normal test should be less than 200 nanograms per milliliter, but Airyana’s test was greater than 1,600 nanograms per milliliter.

Nelson then reviewed 13 slides provided by Turner that showed Airyana’s lung filled with inflammatory cells (evidence of pneumonia), how blood flow was blocked, clots in blood vessels in the retina and optic nerve sheath, and clots in the dura, skull cavity, subarachnoid space near the brain and on the brain itself.

“Is retinal hemorrhaging and optic nerve sheath hemorrhaging specific to any type of abusive head trauma?” Nelson asked.

“No,” Turner replied.

Barnard says many pieces of information missing from report

Barnard began his cross-examination by confirming that Turner reported bronchopneumonia was found in Airyana’s lungs, compromising her ability to breathe. He said Turner said the disease process began with viral pneumonia, followed by bacterial pneumonia.

“Doctor, point to me in that report where it says this disease process began before Jan. 20,” Barnard asked.

“I don’t state that explicitly, except in my photo micrographs, where I show the endothelial cells and the healing promise,” Turner replied.

Barnard asked again for Turner to pointed out in the report where it says the disease process began before Jan. 20.

“It’s not in there, is it?” he asked.

“It’s in the photo micrographs, which is part of my report,” she said. “I submitted those with the report.”

“It’s not in your report,” Barnard repeated.

“That is a photo micrograph. It’s part of my report,” Turner repeated.

Later, Barnard said, “Doctor, point out to me where it says in this eight-page report the words ‘diabetic ketoacidosis.’”

“It doesn’t say that,” Turner said.

“Point out to me in this report where it uses the term ‘ketones,’” Barnard said.

“I don’t know if I included that in here,” Turner said.

‘Where does that appear in your report?’

Barnard went on to ask Turner to find in her report references to microthrombi in the eyes, viral pneumonia, bronchopneumonia, pneumonia, impression pneumonia, viral pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia.

“They’re not there,” Turner said.

Barnard asked Turner if she was familiar with Airyana’s health history provided by her family, considering her appearance and well-being before Jan. 20.

“Yes, including a period where she stopped breathing,” Turner said.

“Good point. Where does that appear in your report?” Barnard asked.

“It doesn’t,” she replied.

“If it was it was significant to you, I’m guessing you’d have put it in your report,” Barnard said.

Barnard says Airyana was ‘literally on death’s door’

Barnard described Cardinal Glennon as a place people bring children from some distances because of the resources it has.

“(Airyana was) literally on death’s door,” he said.

Turner said her condition was poor. Barnard said she was lifeless when getting to the hospital and remained that way.

Barnard then said Airyana was given antibiotics to prevent the introduction of the material potentially infectious into her lungs. He went on to say an infectious disease doctor said there was “no clear infectious etiology (cause) for this infant’s decompensation.”

Barnard then switched gears to sepsis, noting no statements in Blessing reports for it.

“Laboratory tests and other vital signs were supportive of sepsis,” Turner said.

“Those findings were not sufficient to rise to the level to cause an entry in the medical record,” Barnard said.

“It also may not have crossed their mind, because their focus may have been elsewhere,” Turner said.

Turner calls no diagnosis of sepsis by hospital ‘a misdiagnosis’

Cardinal Glennon records also had no diagnosis of sepsis, Barnard said.

“They did not consider that in their evaluation of her,” Turner said.

“Did you talk to them?” Barnard said.

“No. It’s not in the record,” Turner said.

“That’s my point. It’s not in the record, even as a suspicion,” Barnard said.

“It was a misdiagnosis,” Turner said.

“Well, that’s your conclusion,” Barnard said. “I don’t suppose that statement appears in your report, does it?”

“I describe the findings of sepsis in my report,” Turner said.

Barnard: ‘The more reports you generate, the more money you make’

Barnard said Turner made closed head injury diagnoses between “two and three dozen times” when she was with the St. Louis Medical Examiner’s Office.

“Since you started your business, you have not come to that conclusion once,” Barnard said.

Turner said she gave one opinion to that effect in the past 12 to 18 months.

Barnard concluded by saying Turner gave a similar diagnosis for a case in Maine.

“You billed for that, didn’t you?” he asked.

“I billed for the work I did,” she replied.

Barnard said the bill for a previously similar case in Quincy was $22,800.

“The more reports you generate, the more money you make,” he said.

“That’s not entirely true,” Turner said.

Barnard read a series of bills in this case to Turner’s business adding up to $12,000. Turner said she was told she would be paid $5,500, regardless of the time she spent on the case.

Petrak: Subdural hemorrhages common when investigating abusive head trauma

Petrak testified to Barnard that abusive head trauma is a recognized medical diagnosis. She said she has been involved with an average of 15 post-mortem cases per year since 2009. Hospital information and an autopsy report are used to review in her post-mortem child abuse cases. She also reviewed police and medical emergency records in Airyana’s case.

The most common findings are subdural hemorrhages when investigating abusive head trauma. Retinal hemorrhages also is commonplace. The most life-threatening of abusive head trauma injuries is brain swelling, Petrak said.

Barnard asks Petrak if sepsis, which she defined as overwhelming infection in the body, is consistent with abusive head trauma? Petrak said no.

Petrak said the brain injuries were severe, as well as injuries to the brain tissue and the optic nerve sheath. No infections were found and there was no evidence of a metabolic problem. The subdural and retinal hemorrhages, and the lack of an explanation for any of the injuries, helped her come up with her diagnosis.

Consensus statement on abusive head trauma made in 2018

Petrak explained a consensus statement — a group of experts in the field who do a review and make a statement on a particular medical condition. A consensus statement on abusive head trauma in pediatrics was made in 2018 and supported by the Society for Pediatric Radiology, the American Society of Pediatric Neuroradiology and the American Academy of Pediatrics, among others.

Petrak said it clarified what abusive head trauma is and that many alternate theories have no evidence to base them on.

“Was this a close case to call?” Barnard asked.

“No,” she said. “All the evidence and all of the information there, there really wasn’t any other medical condition that would have explained all of the findings.”

Under cross-examination by Nelson, Petrak said she has testified on the behalf of a defense attorney two years ago. She said she has consulted with a defense attorney “maybe once” in the past year. She primarily testified for the prosecution “over 150 times” in the past year. Petrak said she has agreed with the pathology report every time when investigating abusive head trauma cases in the past two years.

She said she did not review the microscopic slides in this case and typically would not. She says the pathologist already has reviewed them.

“The pathologist you typically agree with?” Nelson says.

THE PODCAST

No podcast is available for this episode.